The new iPad processor A5X is about 36% larger than the A5 processor of the previous iPad generation. Both the A5x and the A5 are using 45nm process. This was likely designed in order to get the largest number of working dies from each wafer. Apple will probably do a shrink to the 32nm process when the process becomes more mature. The process shrink will have the benefits of lower power usage which will reduce iPad over-heating and will increase battery time.

It is interesting that while intel already uses 32nm, Apple still uses Samsung's at 45nm.

"A5X measures roughly 163 square millimeters, compared to about 120 square millimeters for the standard A5. Both chips use identical ARM processor cores, but the A5X adds four PowerVR SGX543MP4 graphics cores, which are paired in groups of two and then symmetrically opposed to each other on the floor plan.

The A5X, like the standard A5, features two application processor cores and operates at 1 GHz., UBM TechInsights said. But the A5X includes more DDR interfaces and more architecture added for the handling of quad-core GPU..."

The beefed up DRAM memory interface and the increased graphic processing power is required for the enhanced display of the new iPad.

Ron Maltiel

The New iPad - Generation 3 Teardown and Apple A5X IC Analysis

http://ubmtechinsights.com/teardowns/new-apple-ipad-gen3-teardown-analysis/

Since its introduction almost nearly two years ago, the iPad not only ushered in a new age of consumer electronics by bringing visibility to the ‘tablet’ product, but it also quickly dominated its market. By the end of 2010, Apple had sold over 15 million iPads and, despite strong competition from products released by Motorala and Samsung, held a 75% share of overall sales of tablets.

Approximately one year later, Apple introduced the iPad 2 to much fanfare. Improving on the original, Apple increased the processor power with the introduction of the Apple A5 dual-core processor. As expected by many, the iPad 2 also sold in the millions of units.

Apple had begun a pattern of lifecycles for iPads, so it was no surprise on March 7th that the third generation of the iPad (referred to by Apple as the “new iPad” or “the iPad 3” by others to avoid confusion) was announced. Building upon Apple’s history of iterative improvements in new products, the new iPad boasted of a new Retina display (with 2048 x 1536 resolution, 3.1 total million pixels and 264 pixels per inch) promising the most vibrant iPad to date, a 5 MP backside illuminated sensor that would make the iPad comparable to high-end digital cameras, and the introduction of a brand new processor, the Apple A5X. The new iPad, or iPad 3, was also the first Apple device to the LTE-enabled (or 4G), marking Apple’s first foray into the fastest wireless baseband spectrum available.

When we picked up the device on March 16th, we took it to our lab as soon as we could to take it apart and analyze what makes the new iPad, or iPad 3, different from its predecessors. Of note, was the understanding that some major semiconductor manufacturers were going to walk out with some major design wins, as a product that’s expected to sell in the tens of millions should obviously help their bottom line. The first major design winner in the new Apple iPad is a long time partner in Broadcom. Broadcom picked up three major design wins, two of which for their touchscreen controllers (the BCM5974, which have been found in the iPad 2 and the BCM5973 which was found in the previous iPads and the 1st generation of the iPhone). The other major design win comes for their four-in-one combo wireless chip, the BCM4330, which was also found in the iPhone 4S. Below are some images of the Broadcom ICs we’ve analyzed using our de-encapsulation (decap) process.

Broadcom ICs

A closer look inside the Qualcomm MDM9600 and their other design wins

Qualcomm was another major design winner. Qualcomm has benefitted greatly from Apple’s move into the CDMA market (such as when they introduced the Verizon iPhone 4). When Apple made the decision to offer CDMA versions of their product, it gave Qualcomm the foot in the door it needed to usurp Infineon as the baseband/wireless transceiver provider for them. Since the CDMA iPhone 4, Qualcomm has gotten design wins in the iPad 2 and became the sole IC provider for the iPhone 4S. With the new iPad, Qualcomm gets its LTE Chipset, the MDM9600 designed into it. Qualcomm also provides the RTR8600 transceiver chipset and the PM8028 power management IC. The PM8028 was found within the iPhone 4S whereas the RTR8600 is a major design coup for Qualcomm, replacing the socket that was once held by Infineon/Intel. With the RTR8600, Qualcomm has officially replaced each socket previously held by Infineon/Intel.

The Qualcomm MDM9600 measures in at a die size of approximately 89.89 mm². This LTE Chipset from Qualcomm’s “Gobi” family of embedded data connectivity platforms is compatible across CDMA, HSPA+ and LTE bands and meets Apple’s needs of having a modem that can switch between 3G and 4G seamlessly.

Qualcomm PM8028

Qualcomm RTR8600

Other devices of interest

Apple is well-known for branding IC’s with their recognizable trademark. Either in an effort to prevent competitors from learning about their design selections, or agreements they have in place with manufacturers, Apple devices tend to have components where the manufacturer is not easily determined. Fortunately, due to our decap process, we can find out the secrets inside these chips.

Apple 338S0987 – Cirrus Logic CLI1560B0 Audio CODEC

This device was also found within the iPhone 4S and continues Cirrus Logic’s relationship with the Apple that began back with the Apple iPhone 3GS.

The Image Sensors

In a surprising discovery, both image sensors found in the new iPad were developed by Omnivision.

Omnivision provides the OV297AA 0.3 MP camera and the OV290B 5 MP Backside Illumination Camera Module.

Power Management

Finally, confirmed within the new Apple iPad, is another design win for Dialog. The D1974 power management unit makes it the third unique PMU to be used in each generation of iPad.

The Memory

Hynix H2DTDG8UD1MYR – 16GB of NAND Flash Memory Package

Apple is known for multi-sourcing its manufacturers of Flash for their products. It could very well be Toshiba in one iPad and Samsung in another. In the case of our iPad, we see the same NAND Flash that we also found in the 16GB model of the iPad 2 from Hynix. This memory package features two 64 Gbit dies to equal 16 GBytes of memory.

The same can be said about other system memory. Other teardowns of the new iPad have shown memory packages from Toshiba. In our iPad, we discovered a Micron multichip memory package. The same case exists for the DDR2 SDRAM that comprises the system memory. Some iPads have seen Elpida devices to make up the 1 GB of Low Power DDR2. Our iPad features Samsung memory. Considering the amount of litigation taking place between Samsung and Apple these days, it’s still surprising how such fierce rivals at the product level can work together at the semiconductor level. All this indicates that Apple has taken a strategy of using multiple suppliers from multiple regions to prepare for any difficulty that could arise in their supply chain. Prior to his appointment as CEO, Tim Cook was well known amongst Apple’s employees for his proactive approach to the Supply Chain. That influence still exists today as seen in the new iPad.

The Others

Other major design winners include Skyworks with two major socket wins for their FEMs, Triquint Semiconductor with one win for their power amplifier modules, and Texas Instruments with two socket wins that support the touchscreen. One surprise design winner was Fairchild Semiconductor, who found two of their MOSFET components within the new iPad.

Feature Specs

Apple A5X Processor - Dual-core applications processor with quad-core graphics processor

Retina display - 2048 x 1536 resolution, 3.1 total million pixels, 264 pixels per inch

5 MP backside illuminated sensor - 5-element lens, IR filter, and ISP built into the A5X chip

1080p video recording

4G LTE

Microphone for voice dictation

Primary Component Listing

Broadcom BCM4330 – Bluetooth 4.0, Dual-Band WLAN, FM Transceiver

Broadcom BCM5973 - Touchscreen Controller

Texas Instruments CD3240B0 - Touchscreen Line Driver

Broadcom BCM5974 – Capacitive Touchscreen Controller

Qualcomm PM8028 – Power Management IC

Qualcomm RTR8600 – GSM / CDMA / W-CDMA / LTE Transceiver + GPS chipset

Triquint TQM7M5013 – Gobi Single-mode Modem

Qualcom PM8028 – Quad-Band GSM / GPRS / EDGE-Linear Power Amplifier Module

Qualcomm MDM9600 - LTE Modem Chipset

Apple 338S0987 - Cirrus Logic CLI1560B0 – Audio CODEC

Inside the Apple A5X

Inside the new Apple iPad, or iPad 3, lies a modified A5 processor dubbed the A5X. This modified A5 processor still features two application processor cores and operates at 1 GHz, however, the architecture has been modified to include quad-core graphics. It is stated by Apple to feature the PowerVR SGX543MP4 GPU (the same graphics processor core found in the Playstation Vita). From our decap, right away, you can see that the A5X processor is larger in area than its predecessor. The distinctive die mark also matches that of Samsung-manufactured devices indicating that, once again, Apple has decided to partner with its tablet adversary.

A5X Processor Floorplan

A5 Processor Floorplan

Commentary on Semiconductor industry at the confluence of Process, Product, and Circuits design

Contact Info.

Semiconductor Information and Business News at http://maltiel-consulting.com/

mailto:ron@maltiel-consulting.com

Phone / Fax : (408) 446 - 3040

mailto:ron@maltiel-consulting.com

Phone / Fax : (408) 446 - 3040

Thursday, March 22, 2012

Wednesday, March 21, 2012

Are Japan's Fabs stuck above 28nm Process Technology?

One of the casualties of the $10 Billion cost of developing new semiconductor technologies is Japan's semiconductor industry as is detailed below.

Ron Maltiel

Japan's aging semiconductor industry revealed by 2011 earthquake

http://www.electroiq.com/articles/sst/2012/03/japans-aging-semiconductor-industry-revealed-by-2011-earthquake.html

March 20, 2012 -- One year ago, Japan's semiconductor industry was rocked by a devastating earthquake and tsunami. However, the real disaster for Japan's chip industry occurred during the years before the earthquake -- a period when the country lost its status as one of the world's leading semiconductor manufacturing regions, according to the IHS iSuppli Semiconductor Value Chain Service.

The limited impact of the quake on the global semiconductor industry dramatically illustrated Japan diminished status in the worldwide chip hierarchy and underscored the pressing need for the country to revitalize its business in this area, said Len Jelinek, director and chief analyst for semiconductor manufacturing at IHS.

Suppliers headquartered in Japan accounted for more than one quarter of global semiconductor revenue in 2003, commanding a 27% share. During the next eight years, Japan's share suffered a general decline, dropping 8 points to 19% in 2011 (see the figure).

Semiconductor Revenue

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 % of Global

27.0% 25.4% 23.4% 22.3% 23.4% 23.5% 21.4% 20.4% 18.7%

Figure. Share of Global Semiconductor Revenue Held by Suppliers Headquartered in Japan (Share of Global Revenue in U.S. Dollars). SOURCE: IHS iSuppli March 2012.

Of the major global semiconductor manufacturing regions, Japan now has the smallest number of number of advanced 300mm wafer fabs and the largest number of mature 6" wafer fabs. Companies in Japan have resisted the trend of closing mature facilities and either outsourcing manufacturing or rebuilding manufacturing facilities to current state-of-the-art facilities. Once one of the worlds most advanced semiconductor producers, Japans semiconductor manufacturing operations have become senescent relative to the rest of the world.

In the aftermath of the disaster, the immediate concern was that the semiconductor supply chain would grind to a halt. Massive component shortages were predicted with the potential for recovery pushed out as far as a year. However, by most accounts, things are now back to normal. Of the damaged manufacturing facilities, only one operated by Freescale Semiconductor was shut down permanently after the disaster.

Freescale previously had announced that it intended at the end of 2012 to close the fab in Sendai, an older 6-inch facility that originally manufactured analog products. The earthquake simply hastened the closure.

It is now clear that the impact of the earthquake and tsunami on the global semiconductor market fell far short of some prognosticators' dire predictions.

Unfortunately for Japanese semiconductor companies, the disaster uncovered an issue that had been known but not openly acknowledged: Japan is no longer in a leadership position for the manufacturing of semiconductor components. The long-overdue revitalization of the Japanese semiconductor industry has surfaced as the real issue.

In February, a proposal emerged to address Japan's semiconductor industry weakness that called for the consolidation of manufacturing operations at semiconductor giants Renesas, Fujitsu and Panasonic.

The plan separates out design and manufacturing into two separate companies. Furthermore, the proposal calls for a large capital injection to revitalize the manufacturing company.

Sadly, the plan is really a well-disguised roadmap for significant reduction in semiconductor manufacturing.

Can the plan actually lead to the revitalization of wafer manufacturing in Japan? IHS believes it is highly unlikely.

As the leading chip manufacturing companies transition to sub-28-nanometer manufacturing, Japan is facing the fact that it currently has no company capable of volume manufacturing using this advanced technology node. History has shown that success is driven by experience. Without a strong technical platform on which to gain experience and move forward, there is little chance of the country achieving the transition to sub-28-nanometer production.

How will the semiconductor industry reshape itself? Will Japan's focus shift to design?

Only time will determine the answer, but the probability of Japan successfully sustaining its mature manufacturing engine diminishes with each passing day.

Ron Maltiel

Japan's aging semiconductor industry revealed by 2011 earthquake

http://www.electroiq.com/articles/sst/2012/03/japans-aging-semiconductor-industry-revealed-by-2011-earthquake.html

March 20, 2012 -- One year ago, Japan's semiconductor industry was rocked by a devastating earthquake and tsunami. However, the real disaster for Japan's chip industry occurred during the years before the earthquake -- a period when the country lost its status as one of the world's leading semiconductor manufacturing regions, according to the IHS iSuppli Semiconductor Value Chain Service.

The limited impact of the quake on the global semiconductor industry dramatically illustrated Japan diminished status in the worldwide chip hierarchy and underscored the pressing need for the country to revitalize its business in this area, said Len Jelinek, director and chief analyst for semiconductor manufacturing at IHS.

Suppliers headquartered in Japan accounted for more than one quarter of global semiconductor revenue in 2003, commanding a 27% share. During the next eight years, Japan's share suffered a general decline, dropping 8 points to 19% in 2011 (see the figure).

Semiconductor Revenue

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 % of Global

27.0% 25.4% 23.4% 22.3% 23.4% 23.5% 21.4% 20.4% 18.7%

Figure. Share of Global Semiconductor Revenue Held by Suppliers Headquartered in Japan (Share of Global Revenue in U.S. Dollars). SOURCE: IHS iSuppli March 2012.

Of the major global semiconductor manufacturing regions, Japan now has the smallest number of number of advanced 300mm wafer fabs and the largest number of mature 6" wafer fabs. Companies in Japan have resisted the trend of closing mature facilities and either outsourcing manufacturing or rebuilding manufacturing facilities to current state-of-the-art facilities. Once one of the worlds most advanced semiconductor producers, Japans semiconductor manufacturing operations have become senescent relative to the rest of the world.

In the aftermath of the disaster, the immediate concern was that the semiconductor supply chain would grind to a halt. Massive component shortages were predicted with the potential for recovery pushed out as far as a year. However, by most accounts, things are now back to normal. Of the damaged manufacturing facilities, only one operated by Freescale Semiconductor was shut down permanently after the disaster.

Freescale previously had announced that it intended at the end of 2012 to close the fab in Sendai, an older 6-inch facility that originally manufactured analog products. The earthquake simply hastened the closure.

It is now clear that the impact of the earthquake and tsunami on the global semiconductor market fell far short of some prognosticators' dire predictions.

Unfortunately for Japanese semiconductor companies, the disaster uncovered an issue that had been known but not openly acknowledged: Japan is no longer in a leadership position for the manufacturing of semiconductor components. The long-overdue revitalization of the Japanese semiconductor industry has surfaced as the real issue.

In February, a proposal emerged to address Japan's semiconductor industry weakness that called for the consolidation of manufacturing operations at semiconductor giants Renesas, Fujitsu and Panasonic.

The plan separates out design and manufacturing into two separate companies. Furthermore, the proposal calls for a large capital injection to revitalize the manufacturing company.

Sadly, the plan is really a well-disguised roadmap for significant reduction in semiconductor manufacturing.

Can the plan actually lead to the revitalization of wafer manufacturing in Japan? IHS believes it is highly unlikely.

As the leading chip manufacturing companies transition to sub-28-nanometer manufacturing, Japan is facing the fact that it currently has no company capable of volume manufacturing using this advanced technology node. History has shown that success is driven by experience. Without a strong technical platform on which to gain experience and move forward, there is little chance of the country achieving the transition to sub-28-nanometer production.

How will the semiconductor industry reshape itself? Will Japan's focus shift to design?

Only time will determine the answer, but the probability of Japan successfully sustaining its mature manufacturing engine diminishes with each passing day.

Labels:

28nm,

Design,

earthquake,

expert,

Fab,

Fabrication,

Japan,

Manufacturing,

Process,

testify,

witness

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

Is Samsung Cutting Qualcomm's Cord?

Samsung continues its successful juggernaut of supporting competitors chips while introducing its own products. Their advances in process and circuit technology such as Through Silicon Via (TSV) will strengthen their edge.

Is this a lesson for Intel on how to leverage their technology edge...

Ron Maltiel

Samsung cuts dependence on Qualcomm

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/tech/2012/03/129_107204.html

By Kim Yoo-chul, 03-19-2012

Smartphone maker plans to use in-house chips for Galaxy S III

Samsung Electronics will use its single-chip solutions for its next smartphone, the Galaxy S III, to lower dependence on U.S. chipmaker Qualcomm.

The move comes as Samsung, the world’s top memory chipmaker, aggressively shifting focus to more profitable and less-volatile non-memory chips.Memory chips like DRAMs and NAND flashes are used to read and write data with these chips being commoditized. Thus they are cheap, compared with non-memory chips. Non-memories are to control an entire computing system and require advanced chip-making technology.

``Samsung’s single-chip solution is a combination of long-term evolution (LTE), telecommunications and W-CDMA functions,’’ a high-ranking company executive said Monday.The firm’s Exynos-branded quad-core mobile application processors (APs) are to be equipped in the Galaxy S II’s successor, according to the executive.``We don’t think there will be big technology-related problems as we have already tested our telecommunications chips in some smartphones and tablets for consumers in North America. Also, Google’s first reference mobile, the Galaxy Nexus, is using Samsung's telecom chips,’’ said the executive.

``Samsung has a stronger intent to lower its dependence on Qualcomm and our technicians believe that we have made significant progress in producing logic-based chips for high-end devices, combined logic and memory chips for graphic controllers and core communication chips for Internet-enabled consumer devices,’’ said the executive.

Amid the explosive growth for LTE-enabled smartphones globally, the decision could hurt San Diego-based Qualcomm in the mid- to long-term, according to analysts.``Samsung is paying huge amounts to Qualcomm in return for using its single-chip solutions in strategic digital devices, however, Qualcomm is gradually losing its edge,’’ said another Samsung executive. Both executives asked not to be identified as they don’t have the right to officially speak to the media.

Samsung, which was the world’s biggest smartphone seller last year, plans to sell 250 million smartphones this year, up 25 percent from its earlier target of 200 million.

Ambitious Samsung, uneasy Qualcomm

So far, Samsung Electronics is an earnings propeller for Qualcomm because the American firm was the sole provider of one-chip solutions. ``It was believed that Qualcomm chips had greater stability and suited easy upgrades. But, that’s the old story,’’ said the Samsung executives.

In line with its plan, Samsung is improving ``through silicon via’’ (TSV) memory stocking technology. ``Our long-term plan is clear. Using Samsung solutions for Samsung products.’’

To prevent Qualcomm from losing one of its top customers, it recently announced the launch of its fifth-generation Gobi reference platform that seeks to pack support nearly all major worldwide mobile standards into a single chip. Based on the company’s Gobi LTE wireless baseband modems, the MDM9615 and MDM9215 deliver fast LTE connectivity with backwards compatibility to both HSPA+ and EV-DO networks, Qualcomm insists.

``This will allow support for regional LTE frequencies with backwards compatibility to existing 2G and 3G technologies, allowing Gobi LTE devices to connect to faster LTE network locallys and stay connected to the Internet globally on 3G networks worldwide,’’ it added.

Both Qualcomm officials in South Korea, and Samsung Electronics spokesman Ken Noh declined to comment on the Korean firm’s plans.

Samsung’s transition towards becoming a solutions provider and a chip supplier is strengthening as its mobile head Shin Jong-kyun is injecting more resources to expand the management of its own telecom chips.``Our division is not just to produce smartphones and tablets. In order to diversify portfolios, our division should do better for telecom chips,’’ said Shin.

The chip division is handling mobile APs and the head of the company’s device solution unit, which encompasses flat-screens and memory chips, recently told The Korea Times that its mobile AP-making factory in Austin, Texas, became fully operational last year. Apple’s i-devices use Samsung’s mobile APs produced at the Austin plant.

The Exynos chip is currently built using a 45-nanometer process but the new Exynos chip will be made with 32-nanometer technology, giving better performance quality without using as much power. Samsung said that in terms of performance, it gives up to 26 percent more than the current 45-nanometer chip, with battery life improved by half. The new version will be used in the Galaxy S III.

This in itself is good news for consumers who rely on battery performance when choosing devices.``The development of quad-core mobile APs is finalized and the decision to make one-chip solutions was by Shin,’’ said an executive at the company’s semiconductor division.``If Samsung successfully strengthens its management for telecommunications chips, then it expects to see more revenue from smartphones and tablets. That’s the scenario we hope,’’ said the unnamed executive.

Samsung has a cross-licensing deal with Qualcomm until 2024 to use the American firm’s single-chip solutions.

Switzerland-based brokerage UBS has raised its target for Samsung Electronics shares to 1.48 million won citing a rising shares in smartphones.

Is this a lesson for Intel on how to leverage their technology edge...

Ron Maltiel

Samsung cuts dependence on Qualcomm

http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/tech/2012/03/129_107204.html

By Kim Yoo-chul, 03-19-2012

Smartphone maker plans to use in-house chips for Galaxy S III

Samsung Electronics will use its single-chip solutions for its next smartphone, the Galaxy S III, to lower dependence on U.S. chipmaker Qualcomm.

The move comes as Samsung, the world’s top memory chipmaker, aggressively shifting focus to more profitable and less-volatile non-memory chips.Memory chips like DRAMs and NAND flashes are used to read and write data with these chips being commoditized. Thus they are cheap, compared with non-memory chips. Non-memories are to control an entire computing system and require advanced chip-making technology.

``Samsung’s single-chip solution is a combination of long-term evolution (LTE), telecommunications and W-CDMA functions,’’ a high-ranking company executive said Monday.The firm’s Exynos-branded quad-core mobile application processors (APs) are to be equipped in the Galaxy S II’s successor, according to the executive.``We don’t think there will be big technology-related problems as we have already tested our telecommunications chips in some smartphones and tablets for consumers in North America. Also, Google’s first reference mobile, the Galaxy Nexus, is using Samsung's telecom chips,’’ said the executive.

``Samsung has a stronger intent to lower its dependence on Qualcomm and our technicians believe that we have made significant progress in producing logic-based chips for high-end devices, combined logic and memory chips for graphic controllers and core communication chips for Internet-enabled consumer devices,’’ said the executive.

Amid the explosive growth for LTE-enabled smartphones globally, the decision could hurt San Diego-based Qualcomm in the mid- to long-term, according to analysts.``Samsung is paying huge amounts to Qualcomm in return for using its single-chip solutions in strategic digital devices, however, Qualcomm is gradually losing its edge,’’ said another Samsung executive. Both executives asked not to be identified as they don’t have the right to officially speak to the media.

Samsung, which was the world’s biggest smartphone seller last year, plans to sell 250 million smartphones this year, up 25 percent from its earlier target of 200 million.

Ambitious Samsung, uneasy Qualcomm

So far, Samsung Electronics is an earnings propeller for Qualcomm because the American firm was the sole provider of one-chip solutions. ``It was believed that Qualcomm chips had greater stability and suited easy upgrades. But, that’s the old story,’’ said the Samsung executives.

In line with its plan, Samsung is improving ``through silicon via’’ (TSV) memory stocking technology. ``Our long-term plan is clear. Using Samsung solutions for Samsung products.’’

To prevent Qualcomm from losing one of its top customers, it recently announced the launch of its fifth-generation Gobi reference platform that seeks to pack support nearly all major worldwide mobile standards into a single chip. Based on the company’s Gobi LTE wireless baseband modems, the MDM9615 and MDM9215 deliver fast LTE connectivity with backwards compatibility to both HSPA+ and EV-DO networks, Qualcomm insists.

``This will allow support for regional LTE frequencies with backwards compatibility to existing 2G and 3G technologies, allowing Gobi LTE devices to connect to faster LTE network locallys and stay connected to the Internet globally on 3G networks worldwide,’’ it added.

Both Qualcomm officials in South Korea, and Samsung Electronics spokesman Ken Noh declined to comment on the Korean firm’s plans.

Samsung’s transition towards becoming a solutions provider and a chip supplier is strengthening as its mobile head Shin Jong-kyun is injecting more resources to expand the management of its own telecom chips.``Our division is not just to produce smartphones and tablets. In order to diversify portfolios, our division should do better for telecom chips,’’ said Shin.

The chip division is handling mobile APs and the head of the company’s device solution unit, which encompasses flat-screens and memory chips, recently told The Korea Times that its mobile AP-making factory in Austin, Texas, became fully operational last year. Apple’s i-devices use Samsung’s mobile APs produced at the Austin plant.

The Exynos chip is currently built using a 45-nanometer process but the new Exynos chip will be made with 32-nanometer technology, giving better performance quality without using as much power. Samsung said that in terms of performance, it gives up to 26 percent more than the current 45-nanometer chip, with battery life improved by half. The new version will be used in the Galaxy S III.

This in itself is good news for consumers who rely on battery performance when choosing devices.``The development of quad-core mobile APs is finalized and the decision to make one-chip solutions was by Shin,’’ said an executive at the company’s semiconductor division.``If Samsung successfully strengthens its management for telecommunications chips, then it expects to see more revenue from smartphones and tablets. That’s the scenario we hope,’’ said the unnamed executive.

Samsung has a cross-licensing deal with Qualcomm until 2024 to use the American firm’s single-chip solutions.

Switzerland-based brokerage UBS has raised its target for Samsung Electronics shares to 1.48 million won citing a rising shares in smartphones.

Labels:

Design,

Device,

expert,

Fabrication,

Intel,

Qualcomm,

Samsung,

Smart Phone,

Smartphone,

testify,

Through Silicon Via,

TSV,

witness

Monday, March 19, 2012

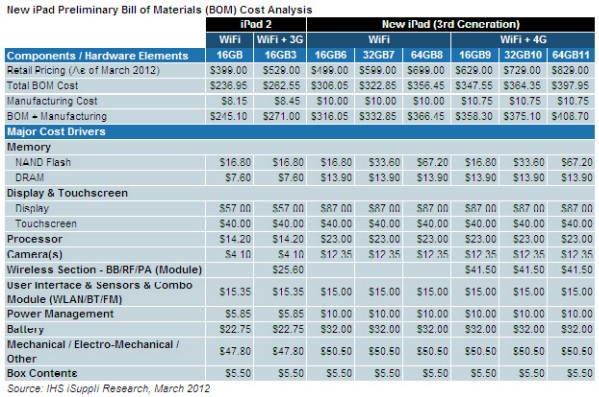

iPad Teardown - Flash NAND Memory is a Major Profit Source

IHS iSuppli's teardown of the new iPad, equipped with 32 Gigabytes (GB) of NAND flash memory and 4G Long Term Evolution (LTE) wireless capability, carries a bill of materials (BOM) of $364.35. When the $10.75 manufacturing costs are added in, the cost to produce the new iPad rises to $375.10. The BOM of the 16GB 4G LTE version amounts to $347.55, and the 64GB version is estimated at $397.95.

(more below)

The $364.35 BOM represents 50 percent of the $729.00 retail price of the 32GB LTE version of the new iPad.

“The NAND flash memory is one of the key profit-generating components for Apple in the new iPad line, as it has been in previous iPads and in the iPhone family,” Rassweiler noted. “Apple makes far and away more money in selling consumers NAND flash than NAND flash manufacturers make selling it to Apple. And the more flash in the iPad, the higher the profit margin there is for Apple.”

For example, the retail price of the 32GB LTE-enabled new iPad is $100 higher than the 16GB model. However, Apple’s BOM for the 32GB version is only $16.80 more compared to the 16GB model.

Ron Maltiel

New iPad 32GB + 4G Carries $364.35 Bill of Materials

http://www.isuppli.com/Teardowns/News/Pages/New-iPad-32-GB-4G-Carries-364-35-Bill-of-Materials.aspx

Andrew Rassweiler, March 16, 2012

The new iPad, equipped with 32 Gigabytes (GB) of NAND flash memory and 4G Long Term Evolution (LTE) wireless capability, carries a bill of materials (BOM) of $364.35. When the $10.75 manufacturing costs are added in, the cost to produce the new iPad rises to $375.10. The BOM of the 16GB 4G LTE version amounts to $347.55, and the 64GB version is estimated at $397.95.

The $364.35 BOM represents 50 percent of the $729.00 retail price of the 32GB LTE version of the new iPad.

The very lowest-end version of the new iPad, with 16GB memory and no LTE, carries a combined BOM and manufacturing cost of $316. The highest-end model, with 64GB memory and integrated LTE, has a total BOM and manufacturing expense of $408.70.

Please note that these teardown assessments are preliminary in nature, account only for hardware and manufacturing costs and do not include additional expenses such as software, licensing, royalties or other expenditures.

The new iPad is more expensive to produce than the iPad 2 at the time of product launch, even though the retail price points are the same. The 32GB LTE model’s BOM is nearly 9 percent higher than an iPad 2 equipped with 32GB and 3G wireless, which carried a cost of approximately $335 at the time of product launch. Major factors driving up the BOM include the addition of the high-resolution Retina display, LTE wireless and a larger-capacity battery.

The table below summarizes the major components in the new iPad.

Among all component suppliers, Samsung Electronics continues its reign as the big winner in the individual iPad analyzed by the IHS iSuppli Teardown Analysis Service. Samsung supplied both the display and the applications processor. The new iPad’s Retina display represents the most expensive single component in the tablet, at $87, while the applications processor costs an estimated $23. Combined, this gives Samsung a 30.2 percent share of the 32GB LTE version of the new iPad’s bill of materials, the largest for any supplier.

In the individual new iPad analyzed, the NAND flash was supplied by Toshiba Corp. However, Samsung also is a source of NAND for the new iPad. In a 32GB LTE iPad where Samsung is also the supplier of the NAND, Samsung’s share of the BOM rises by $33.60 to a total of $143.60, amounting to 39.4 percent of the total BOM. However, Toshiba, Hynix Semiconductor and others also are all NAND suppliers to Apple, and each will claim a portion of those revenues.

Although we are not certain, IHS believes that the battery cells are supplied by Samsung. If this turns out to be the case, Samsung will account for nearly 50 percent of the new iPad’s BOM.

“The Retina display represents the centerpiece of the new iPad and is the most obvious enhancement in features compared to previous-generation models,” said Andrew Rassweiler, senior principal analyst, teardown services, at IHS. “The first two generations of the iPad employed the same type of display—a screen with resolution of 1,024 by 768 pixels. For the third-generation new iPad, Apple has taken a significant step up in display capabilities and expense, at four times the resolution and 53 percent more cost.”

The new iPad’s Retina display has a resolution of 2,048 by 1,536 pixels. It costs $87, compared to $57 for the screen used in the iPad 2. The $87 cost accounts for 24 percent of the BOM of the new iPad with 32GB NAND and LTE, making the Retina display the most expensive single component in the tablet.

As IHS announced in a previous release, we believe Apple likely has qualified three sources for the display in the new iPad: Samsung, LG Display and Sharp Corp. (see Apple Display Spending Expected to Nearly Double in 2012, Helped by Surging iPad Sales). However, it is likely that all the volume shipments of the new iPad display are currently coming from Samsung. In line with this view, the individual new iPad torn down by IHS includes a Samsung-sourced Retina display.

The touch screen for the new iPad costs an estimated $40, or 10.9 percent of the total BOM. As in the iPad 2, the main suppliers in this area are still TPK, Wintek and Chi Mei.

The wireless section costs $41.50 and accounts for 11.4 percent of the BOM. Because this section provides support for the LTE capabilities of the new iPad, it is significantly more expensive than the $25.60 wireless section of the iPad 2, which supported the 3G air standard. The big winner in this section is Qulcomm Inc., whose MDM9600 baseband processor provides the core LTE functionaility. IHS believes that the wireless section is the same for both AT&T and Verizon versions of the new iPad, although that hasn’t been confirmed yet.

The A5X applications processor costs $23, and represents 6.3 percent of the total BOM. Samsung manufactures the A5X for Apple. However, for this device, Samsung serves as a foundry partner to Apple, and not as an independent semiconductor supplier. Apple is the designer and owner of the intellectual property of the A5X, and Samsung manufactures the part on a contract basis. This means that Samsung likely commands a lower margin on the device that it would otherwise.

“The NAND flash memory is one of the key profit-generating components for Apple in the new iPad line, as it has been in previous iPads and in the iPhone family,” Rassweiler noted. “Apple makes far and away more money in selling consumers NAND flash than NAND flash manufacturers make selling it to Apple. And the more flash in the iPad, the higher the profit margin there is for Apple.”

For example, the retail price of the 32GB LTE-enabled new iPad is $100 higher than the 16GB model. However, Apple’s BOM for the 32GB version is only $16.80 more compared to the 16GB model.

The new iPad camera module design and cost is the same as in the iPhone 4 camera module. The two camera modules cost a combined $12.35, representing 3.4 percent of the BOM.

The battery delivers a major upgrade from the previous model. The lithium polymer battery in the new iPad supports 42.5 watt hours, up about 75 percent from 25 watt hours in the iPad 2. However, because of price decreases during the past year, the new battery costs only 40 percent more than the old one, at $32.00, compared to $22.75 for the one in the iPad 2.

Sunday, March 18, 2012

Moore's Law End? (Next semiconductors gen. cost $10 billion)

The next generation of semiconductor technology will cost about $10 billion to create. According to Ana Hunter, vice president of Foundry Services at Samsung, who kicked off the Common Platform Technology Forum 2012 conference in Santa Clara Wednesday this week,(see below) the cost includes process development, factory (fab), circuit design, and the creation of a library and intellectual property to produce complex systems-on-a-chip (SoC).

Currently only TSMC, Global Foundries, and Intel have been spending such amounts. I wonder how Hynix, Sandisk with Toshiba, and Micron are facing these challenges.

In a few years, when it will cost $15 - 20 billion, who will remain in the race? The tremendous cost will slow down the shrinking of semiconductor devices.

Ron Maltiel

Rising Stakes In Semiconductor Game Squeeze Out All But A Few (Forbes.com / Roger Kay)

http://www.forbes.com/sites/rogerkay/2012/03/16/rising-stakes-in-semiconductor-game-squeeze-out-all-but-a-few/

This alliance is about sharing the enormous risks of semiconductor development

Semiconductor development is not for the faint of heart.

Putting together a factory to make the next generation of semiconductors will cost about $10 billion, according to Ana Hunter, vice president of Foundry Services at Samsung, who kicked off the Common Platform Technology Forum 2012 conference in Santa Clara Wednesday this week.

Leading edge semiconductors for sale today have features 32 nanometers (nm) wide. The Common Platform’s next generation has 28nm features, and just this incremental improvement will involve parting with some serious coin. The creation of a library and intellectual property to produce complex systems-on-a-chip (SoC) will cost $250 million. Chip design will run another $100 million, not counting software. And tooling the actual factory will take a cool $7 billion.

And that’s the investment before the first dime of revenue is realized.

The club capable of sustaining this sort of outlay gets more exclusive by the day. Only a few short years ago, there were a half dozen players, back when the tab for membership was a mere $3 billion. Samsung was one of them. Now, it’s down to two foundries (which make chips for others) and one integrated device manufacturer (which makes chips for itself).

The integrated device manufacturer is Intel, which fights a lonely battle, doing all its R&D internally, building its own factories, making its own chips, and selling them to customers who build systems.

The foundries are Taiwanese behemoth TSMC, the incumbent, and GlobalFoundries, the challenger. GlobalFoundries, now fully spun out from AMD, where it used to be the company’s manufacturing branch, picked up Chartered Semiconductor out of Singapore to form the core of the company’s assets. AMD contributed technology to the venture. The main party sustaining GlobalFoundries at the moment is Advanced Technology Investment Company (ATIC), which invests on behalf of the government of Abu Dhabi. ATIC has committed $10 billion to sustain GlobalFoundries through profitability and growth, not to mention building and retrofitting a considerable number of factories pretty much continuously.

But beyond GlobalFoundries and its backers, the Common Platform extends the alliance further. IBM and AMD have worked together for years on chip development, and AMD remains Globalfoundries’ biggest customer. IBM contributes significant intellectual property to the alliance.

Samsung, which arguably competes with GlobalFoundries as a foundry, but also makes chips for itself, has thrown its lot in with the Common Platform, primarily to spread investment risk.

As Hunter of Samsung pointed out, technology choices are fraught with risk. After 28nm, the next “process node,” as they’re called, is 20nm, which is the last stop for so-called “planar structures,” or features laid out flat in two dimensions. After that, to get to 14nm, the Common Platform will need to create 3D features to drop the transistor size one more time. The transition to three-dimensional structures will be difficult and hugely consequential. Intel is already making 3D structures in its 22nm process, and products based on these new chips are due out later this year.

But the alliance has other reasons to hang together beside cost and technology risk.

There’s physical risk, which GlobalFoundries has mitigated by having factories in North America, Europe, and Asia. If an earthquake or tsunami disrupts one region, others can take up the slack. Intel has global production for the same reason.

The British company ARM, not officially a Common Platform member, but a key sponsor of the conference, has more than a passing interest in the success of the Common Platform. ARM architecture powers most smart phones and tablets, and SoC development is focused heavily on this high mobility market, which requires very low power devices. As complexity increases, ARM and its manufacturing partners need to establish a mutual feedback loop to optimize their designs and processes.

The intricacy of continued process node development is stunning.

Gary Patton, VP of IBM’s semiconductor R&D, gave a glimpse of things down the road. He talked of the limits of each successive generation of technology, how each innovation lasts for a decade or so, gets developers to a point, but hits a limit, and other means have to be found to reduce feature size further. Three-dimensional structure, which is next, will last for a decade, he noted, and the use of shorter wavelength light, extreme ultraviolet, will help get down to 10nm. But around 7nm, process node development will reach the limit of atoms.

At that point, lithography — the method of shining light through masks to create physical printed features — will run out of gas. After that, carbon nanotubes will need to take over. IBM has created functional 10nm circuits out of carbon nanotubes. Carbon electronics will begin to allow designers to put electronics and optics on the same wafer.

As a proof point of the possible, IBM has produced 5nm features in the lab.

But make no mistake, in the race for smaller transistors, Intel maintains a growing lead. Where not long ago this advantage was a year to 18 months, in some areas — 3D structures, for example — the gap is stretching toward three to four years. Intel touts its integrated nature as a key factor in this success. And Intel also has its sights set on 5nm.

But this race is a marathon, not a sprint, and Intel is by no means resting on its laurels. ARM is fueling the high growth form factors — smartphones and tablets — and ARM vendors like Qualcomm and Apple all produce in foundries.

The few remaining players in the increasingly exclusive club of those who can afford semiconductor development must bet billions before knowing the payoff. Their imperative: pour money and expertise into squeezing more performance out of processors in less space using less power.

The risks are huge … but so are the rewards of success.

Currently only TSMC, Global Foundries, and Intel have been spending such amounts. I wonder how Hynix, Sandisk with Toshiba, and Micron are facing these challenges.

In a few years, when it will cost $15 - 20 billion, who will remain in the race? The tremendous cost will slow down the shrinking of semiconductor devices.

Ron Maltiel

Rising Stakes In Semiconductor Game Squeeze Out All But A Few (Forbes.com / Roger Kay)

http://www.forbes.com/sites/rogerkay/2012/03/16/rising-stakes-in-semiconductor-game-squeeze-out-all-but-a-few/

This alliance is about sharing the enormous risks of semiconductor development

Semiconductor development is not for the faint of heart.

Putting together a factory to make the next generation of semiconductors will cost about $10 billion, according to Ana Hunter, vice president of Foundry Services at Samsung, who kicked off the Common Platform Technology Forum 2012 conference in Santa Clara Wednesday this week.

Leading edge semiconductors for sale today have features 32 nanometers (nm) wide. The Common Platform’s next generation has 28nm features, and just this incremental improvement will involve parting with some serious coin. The creation of a library and intellectual property to produce complex systems-on-a-chip (SoC) will cost $250 million. Chip design will run another $100 million, not counting software. And tooling the actual factory will take a cool $7 billion.

And that’s the investment before the first dime of revenue is realized.

The club capable of sustaining this sort of outlay gets more exclusive by the day. Only a few short years ago, there were a half dozen players, back when the tab for membership was a mere $3 billion. Samsung was one of them. Now, it’s down to two foundries (which make chips for others) and one integrated device manufacturer (which makes chips for itself).

The integrated device manufacturer is Intel, which fights a lonely battle, doing all its R&D internally, building its own factories, making its own chips, and selling them to customers who build systems.

The foundries are Taiwanese behemoth TSMC, the incumbent, and GlobalFoundries, the challenger. GlobalFoundries, now fully spun out from AMD, where it used to be the company’s manufacturing branch, picked up Chartered Semiconductor out of Singapore to form the core of the company’s assets. AMD contributed technology to the venture. The main party sustaining GlobalFoundries at the moment is Advanced Technology Investment Company (ATIC), which invests on behalf of the government of Abu Dhabi. ATIC has committed $10 billion to sustain GlobalFoundries through profitability and growth, not to mention building and retrofitting a considerable number of factories pretty much continuously.

But beyond GlobalFoundries and its backers, the Common Platform extends the alliance further. IBM and AMD have worked together for years on chip development, and AMD remains Globalfoundries’ biggest customer. IBM contributes significant intellectual property to the alliance.

Samsung, which arguably competes with GlobalFoundries as a foundry, but also makes chips for itself, has thrown its lot in with the Common Platform, primarily to spread investment risk.

As Hunter of Samsung pointed out, technology choices are fraught with risk. After 28nm, the next “process node,” as they’re called, is 20nm, which is the last stop for so-called “planar structures,” or features laid out flat in two dimensions. After that, to get to 14nm, the Common Platform will need to create 3D features to drop the transistor size one more time. The transition to three-dimensional structures will be difficult and hugely consequential. Intel is already making 3D structures in its 22nm process, and products based on these new chips are due out later this year.

But the alliance has other reasons to hang together beside cost and technology risk.

There’s physical risk, which GlobalFoundries has mitigated by having factories in North America, Europe, and Asia. If an earthquake or tsunami disrupts one region, others can take up the slack. Intel has global production for the same reason.

The British company ARM, not officially a Common Platform member, but a key sponsor of the conference, has more than a passing interest in the success of the Common Platform. ARM architecture powers most smart phones and tablets, and SoC development is focused heavily on this high mobility market, which requires very low power devices. As complexity increases, ARM and its manufacturing partners need to establish a mutual feedback loop to optimize their designs and processes.

The intricacy of continued process node development is stunning.

Gary Patton, VP of IBM’s semiconductor R&D, gave a glimpse of things down the road. He talked of the limits of each successive generation of technology, how each innovation lasts for a decade or so, gets developers to a point, but hits a limit, and other means have to be found to reduce feature size further. Three-dimensional structure, which is next, will last for a decade, he noted, and the use of shorter wavelength light, extreme ultraviolet, will help get down to 10nm. But around 7nm, process node development will reach the limit of atoms.

At that point, lithography — the method of shining light through masks to create physical printed features — will run out of gas. After that, carbon nanotubes will need to take over. IBM has created functional 10nm circuits out of carbon nanotubes. Carbon electronics will begin to allow designers to put electronics and optics on the same wafer.

As a proof point of the possible, IBM has produced 5nm features in the lab.

But make no mistake, in the race for smaller transistors, Intel maintains a growing lead. Where not long ago this advantage was a year to 18 months, in some areas — 3D structures, for example — the gap is stretching toward three to four years. Intel touts its integrated nature as a key factor in this success. And Intel also has its sights set on 5nm.

But this race is a marathon, not a sprint, and Intel is by no means resting on its laurels. ARM is fueling the high growth form factors — smartphones and tablets — and ARM vendors like Qualcomm and Apple all produce in foundries.

The few remaining players in the increasingly exclusive club of those who can afford semiconductor development must bet billions before knowing the payoff. Their imperative: pour money and expertise into squeezing more performance out of processors in less space using less power.

The risks are huge … but so are the rewards of success.

Labels:

20nm,

Circuit,

Common Platform,

Design,

Device,

expert,

Fabrication,

GlobalFoundries,

Hynix,

IBM,

Intel,

Micron,

Moore's Law,

Samsung,

SanDisk,

testify,

Toshiba,

witness

Friday, March 16, 2012

When will Flash Memory Market be 2x of DRAMs

Flash memory has been increasing in popularity due to its shrinking size. There were papers presented at the recent ISSCC 2012 that discussed 128GB Flash NAND using 22-18 nm process technology while DRAM technology is at 4GB using 38 nm process technology (http://www.miracd.com/ISSCC2012/WebAP/PDF/AP_Full.pdf) .

This leads semiconductor companies to switch fabs from DRAM to flash. See "Hynix is switching production at a memory plant in China to churn out NAND flash instead of DRAM chips"

It will not be long before the size of the flash semiconductor chip market will be 2x the DRAM market size.

This leads semiconductor companies to switch fabs from DRAM to flash. See "Hynix is switching production at a memory plant in China to churn out NAND flash instead of DRAM chips"

It will not be long before the size of the flash semiconductor chip market will be 2x the DRAM market size.

Thursday, March 15, 2012

Is Resistive RAM (RRAM) The Future Flash Memory?

Below is an overview of Resistive RAM (RRAM) by Bogdan Govoreanu, from IMEC . This new flash memory technolgy is worth watching.

Eli Harrari, Sandisk founder, CEO, and Chairman from its founding until January 2011 in his ISSCC Plenary talk stated that 3D-RRAM " has a real shot at becoming the next big game-changer in the second half of this decade".

Eli Harrari foresaw upcoming changes in non volatile memory. He converted Sandisk from supporting both NOR and NAND flash to only NAND long before other companies saw the upcoming accelerating growth in NAND.

Ron Maltiel

Resistive RAM for next-generation nonvolatile memory

Bogdan Govoreanu, imec Leuven 3/12/2012 1:25 PM EDT

Since its introduction in 1988 by Toshiba1, NAND flash nonvolatile memory has undergone an unprecedented growth, becoming one of today’s technology drivers. Although NAND flash memory has scaled to 1x-nm feature sizes, shrinking cell sizes reduce the number of electrons stored on the floating gate. Resistive RAM (RRAM) provides an alternative. In this article, we review the main performance figures of hafnium-oxide (HfO2)-based RRAM cells4 from a scalability perspective, outlining their strengths as well as the main challenges ahead.

A NAND flash nonvolatile memory cell, usually a floating gate transistor, implements the memory function by charge stored on the floating gate. With a charge transfer mechanism onto/from the storage medium that relies on tunneling and a serial (string) architecture, NAND memory features high operating voltages (with associated chip area consumption for the on-chip voltage generation), rather long cell program/erase (P/E) times, and slow read-access times. These drawbacks are, however, compensated for by the very compact array architecture and extremely low energy-consumption-per-bit operation, which eventually enabled fabrication of high-density memory arrays, at low cost and with a chip storage capacity increasing impressively.

During its extraordinary evolution, NAND flash has often met seemingly insurmountable barriers. Technological, architectural, and design innovations complemented each other, however, enabling continued scaling. Nowadays, NAND flash memory seems to have found the way toward the realm of 1x-nm feature size, with major players fighting for each nanometer of cell shrinkage, not to mention for supremacy. Nevertheless, the scaling of cell size leads to gradual reduction of the number of electrons stored on the floating gate, with a projected number of less than 30 electrons for memorizing a (multilevel) cell state, for an assumed 15-nm feature size2.

Resistive RAM (RRAM), just like phase-change memory (PCM), is emerging as a disruptive memory technology, implementing memory function in a resistance (rather than stored charge), the value of which can be changed by switching between a low and a high level. Although the phenomenon of reversible resistance switching has been since the 1960s, recent extensive research in the field has led to the proposition of several concepts and mechanisms through which this reversible change of the resistance state is possible. The distinctive feature of most RRAM concepts3 consists of the localized, filamentary nature of a conductive path formed in an insulating material separating two electrodes (a metal-insulator-metal (MIM) structure), corresponding to the on-, low-resistance state. This attribute was immediately associated with a high scalability potential, beyond the limits currently predicted for flash memory.

Resistive memory structures

Even if many materials reported to date exhibit good resistive switching properties, the success of a future RRAM technology is critically dependent on the ability to integrate these materials/switching structures into a conventional, supporting baseline technology, with cost as a key success factor. Not surprisingly, fab-friendly and accessible materials such as HfO2, zirconium dioxide, titanium dioxide, tantalum dioxide/ditantalum pentoxide, etc, which showed resistive switching behavior, have received the highest attention.

A thin HfO2 dielectric film sandwiched between two metal electrodes was shown to have resistive switching properties, either uni- or bipolar, depending on the materials used as electrodes and on the method to deposit the active (oxide) film. The bipolar operation of HfO2, requiring voltages of opposite polarity to switch on/off the cell, is believed to be due to the formation of conductive paths (filaments) associated with presence of oxygen vacancies (VO), which can be ruptured/restored through oxygen/VO migration under electric field and/or locally enhanced diffusion. The bipolar operation of HfO2 is preferred for its increased immunity to disturbs and over reset. The formation of the filament (forming, or electroforming) is believed to take place along pre-existing weak spots in the oxide, for instance along the grain boundaries in case of a polycrystalline HfO2, which presumably have larger amount of defects and also a higher oxygen diffusivity compared to the bulk of the material.5,6

An alternative approach is to use a metal/oxide material system7 with a reactive (capping) metal, capable of chemically reducing the HfO2. Although a Hf/HfO2 system may seem an obvious choice, selection of hafnium as a cap layer is supported by thermodynamic considerations that indicate a low oxide formation energy, when reducing HfO2. A similar property is found for the titanium/HfO2 case. In the Hf/HfO2 system, hafnium acts as an oxygen buffer layer that allows, under electrical stimuli, the production of oxygen-deficient off-stoichiometric oxide, thus favoring formation of the switching filament. Furthermore, conventional physical vapor deposition (PVD) titanium nitride was used to define the bottom and top electrodes (BE/TE) in a crossbar-patterned configuration.

To achieve best flexibility and controllability of RRAM device operation, the resistive memory structure was connected serially with an nMOS transistor, which acts as a cell selector. Figure 1a shows a top view scanning-electron-microscopy (SEM) picture of a test structure, while high-resolution transmission-electron-microscopy (TEM) cross-sections of the structure along the main directions, visualizing the BE/TE are shown in figure 1b and figure 1c. The smallest fully functional working structures processed4, feature an effective area of around 10 x 10 nm2, defined by the BE width and by the width of the TE/Hf-cap tip resulting after the crossbar patterning.

Figure 1: Top SEM-view of a crossbar resistive element (a) and high-resolution TEM cross-sections of the bottom- (b) and top-electrode (c).

The oxide thickness is the main parameter determining the value of the forming voltage (VF), which is typically the highest voltage and needed only once, to get the RRAM cells ready for operation. In contrast, the Set (on-switching) and Reset (off-switching) voltages are lower and, in a common situation, do not depend on oxide thickness. This difference makes it possible that VF can be then reduced by thinning the oxide layer, without interfering with normal cell operation. Furthermore, aggressive oxide thinning may eventually lead to forming-free operation.

The Set/Reset (S/R) voltages, as well as the levels of the on/off states, turn out to be essentially independent not only of oxide thickness, but also of cell size. Although operating the cell in extreme conditions (i.e. with very deep Reset or strong Set switching) may turn these characteristics invalid, the common situation is consistent with the filamentary nature of the conductive path; furthermore, it supports the model of a partial rupture and restoration of the filament during device operation. Eventually, the oxide thickness corresponding to forming-free operation, confirmed experimentally to be in the range of 2 to 2.5 nm, is indicative of the extent of the ruptured portion of the conductive filament.

Electrical performance and reliability

Given the structure asymmetry induced by the presence of the hafnium layer, the RRAM cells are best operated in bipolar mode with positive polarity on TE for the Set and forming operations and with negative polarity on TE for the Reset operation. In this section, we will discuss the most important performance and reliability figures of the HfO2-based RRAM cells.

Switching speed

To measure switching speed, we used a pulsed operation mode, exemplified here for a Reset switching. Thus, stimuli were applied on the sourceline (SL) and wordline (WL) of the serial 1T1R (1-transistor, 1-resistor) test vehicle, while the response was monitored with a digital oscilloscope on a small series resistance attached to the cell bitline (BL; see figure 2a) . The switching was time-confined to a maximum duration given by the width of the SL pulse, i.e. 10 ns. We carefully designed the experimental setup to minimize the impact of the parasitic elements (e.g. capacitances), having a reasonably short system time constant. The resistive element, initially in the on-state, switches to the off-state quickly, leading to a decrease of the signal within just 3 to 4 ns (see figure 2b). When taking into account the impact of the testing environment on the collected waveform, the observed transition time duration gives a higher margin for the intrinsic switching time, which can be shorter.

Figure 2: Schematics of the device under test (DUT), with applied stimuli and collected response (a) and waveforms corresponding to a Reset switching (b), sampled with a LeCroy WavePro 740Zi 4GHz oscilloscope. The 10-ns SL pulse (blue color), which enables switching, in contained in the longer WL pulse (red color) used to open up the transistor’s channel. The Reset switching is confirmed by the read-out (RO) of the cell current, which changes from high value (on-state) before the SL applied pulse to low value (off-state) after the pulse.

On/off window & operating voltages

The on/off window easily exceeds a factor of 10, with modest (<1 V) voltages applied for both S/R operations. Using higher amplitude pulses and switching verification will improve the on/off window by at least two orders of magnitude, as well as enhancing the uniformity of the switching operations (see figure 3a), which may open up paths for multilevel operation.

Figure 3: Typical on/off window (expressed in read-out cell current) achievable with sub-3-V pulsed operation, with verify (a) and Reset pulse amplitude-duration voltage-time trade-off, showing no significant degradation when scaling cell size from 1 um2 down to 10 x 10 nm2 (b). Data are for an oxide film thickness of 10 nm. The dashed lines are guide for the eye. Similar conclusions hold for Set switching (not shown).

The voltage-time dilemma is a popular term used to express the limited ability of RRAM to display nonlinearity. This is however not specific to RRAM, but present in virtually all memory structures, which ideally need to on one hand allow for indefinitely long stability under no or low-electrical stimuli (for retention, read-out and disturbs immunity), while on the other hand providing fast change of state under operating stimuli (for P/E or S/R).

The S/R voltages required to operate these cells thus display the usual trade-off with time. Nevertheless, the pulse amplitude-time dependence shows that the cells can still be operated with voltages well below 3 V, even for pulses as short as 10 ns. Furthermore, in a comparison of large area cells (in the order of 1 um2) with smallest-size cells (of 10 x 10 nm2), the voltage-time characteristics maintain similarity (see figure 3b), which shows that we should expect no considerable performance degradation when considering aggressively scaled structures. Compared to NAND flash, RRAM has the benefits of low-operating voltages.

Reliability: retention & endurance

The usual 10 year requirement for NVM retention is met by most of the RRAM cells, with a median cell reaching this limit at an extrapolated temperature of around 100°C. As expected, retention turns out to be most critical for the on-state, where retention loss is attributed to filament dissolution. Retention improvement is possible through material optimization and careful sealing of the active region with oxygen-free layers.

Endurance tests performed on unoptimized samples showed cycling of at least 10 Mcycles in a single shot. The failure at the end of the tests was, however, recoverable with a stronger stimulus to “unlock” them from the stuck state, and cycled again with adjusted slightly stronger conditions. These facts suggest that careful balancing of the S/R test conditions, next to process improvement, may allow superior reliability and extended device lifetime, which can well exceed billion cycles, even on the smallest device sizes. This figure is far above the conventional requirement for flash memory, pinpointed to 100 kcycles, although reference value for data storage flash is commonly lowered down 10 kcycles, on arguments of practical, as well as economical nature associated with a commodity product.

Scalability, energy consumption, and cell array considerations

The data discussed so far provide evidence of RRAM operation on an effective area of nearly 10-x-10-nm2 without compromising any of the major performance or reliability figures. This size is the smallest reported to date, for HfO2-based RRAM cells and demonstrate cell scalability in the nanometer range, which is beyond scaling limits of NAND flash. Filament formation has been observed experimentally, for instance on TEM pictures, for metallic filaments, such as those formed in nitrous oxide RRAM.

Figure 4: Extracted filament size for 10-x-10-nm2 cells, operated with 10-ns pulse duration. The filament was asssumed cylindrical, with a saturated sub-stochiometric hafnia resistivity.8

In the cells under discussion here, conductive paths presumably formed by oxygen vacancies corresponding to locally lower fractions of oxygen content in the active oxide layer are hard to detect, due to resolution limits of the physical characterization methods. Oxygen-deficient HfO2, however, has a resistivity that correlates with the amount of oxygen-deficiency, but eventually saturates for highly deficient stable sub-oxides, at a value still significantly higher than that of metallic Hf.8 When combined with experimental electrical data corresponding to on-state (measured on the smallest 10 x 10 nm2 HfO2-based RRAM cells), this property allowed extracting the radius of an assumed-cylindrical filament, with a median value of nearly 1 nm. Although an estimate, this result suggests intrinsic scalability of the resistive memory element in the few-nanometer range.

One of the key features of NAND flash technology is the extremely low power required to write/erase a single cell, as it only involves very low (Fowler-Nordheim) tunneling currents. This translates, in spite of the need to use high P/E voltages, into a low energy used to operate a cell, even with the long specific cell P/E times, thus enabling a high throughput in NAND flash. RRAM, by contrast, works at much lower voltages and on/off switching is several orders of magnitude faster than for NAND cells. The current is, however, significantly larger and even if RRAM scores well in comparison with MRAM9 and PCM technologies10,11 there are concerns about the circuit level implications.

Figure 5: Benchmarking of HfO2-based RRAM in relation with existing (NAND flash) and other emerging technologies (MRAM, PCM). An improvement direction implying use of shorter pulses is identified experimentally.4

When we consider the switching energy per bit operation, RRAM is approaching the performance of NAND flash, given the actual peak current levels during switching as high as a few tens of microamps. Crossing below a 10-fJ-NAND flash border would require nanosecond switching speeds, or sub-microamp switching currents; paths to meeting these requirements are currently pursued.

RRAM has device-level characteristics that meet most of the nonvolatile memory requirements. It furthermore shows scalability potential in an area that is thought to be inaccessible to NAND flash. To be able to exploit these strengths at circuit/system level, RRAM must overcome cell read-out interference12 that may cause in erroneous read out of the (HRS) cell state, due to so-called sneak-current paths. Alleviation of this issue requires a bidirectional selector device. The control transistor in a 1T1R structure provides this functionality and it is, in fact, a potential solution for memory arrays in which density is not the main concern. For data storage applications, however, achieving highest memory density should aim at a cell footprint of around 4F2 (with F being the feature size), implementation of which will, most likely, require the use of a two-terminal selector device13 or a rectification function built into the memory element itself (self-rectifying resistive memory). Research achievements in this direction, complemented by consideration of practical possibilities to increase effective density by using 3D architectures14 for meeting cost effectiveness, will eventually determine the success of RRAM as the future nonvolatile memory of choice.

In summary, HfO2-based RRAM shows great promise for future generation nonvolatile memory, offering a fab-friendly option, with performance characteristics that qualify it for a fast, low-voltage, low-energy-consumption memory, with a good and perfectible reliability, as demonstrated for fully-functional 10-nm-size devices and with inferred intrinsic scalability down to a few-nanometer size. Further improvement in reliability and additional “in-the-footprint” or built-in selection functionality set important milestones ahead on the road to becoming tomorrow’s nonvolatile memory.

Note: This article is based on the work reported at IEDM 2011 by the Emerging Memory Devices Program team of imec Leuven.4

References

1. M. Momodomi et al, IEDM Tech. Dig, pp. 412-415, 1988.

2. K. Prall, Proc. NVSMW, pp. 5-10, 2007.

3. R. Waser, IEDM Tech. Dig, pp. 289-292, 2008.

4. B. Govoreanu et al, IEDM Tech. Dig, pp. 729-732, 2011.

5. G. Bersuker et al, IEDM Tech. Dig, pp. 456-459, 2010.

6. U. Brossmann et al, J.Appl.Phys, 85(11): 7646-7654, 1999.

7. B. Govoreanu et al, Ext. Abstr. SSDM, pp. 1005-1006, 2011.

8. E. Hildebrandt et al, Appl.Phys.Lett, 99: 112902, 2011.

9. K. Tsukida et al, ISSCC Dig, pp. 258-259, 2010.

10. R. Annunziata et al, IEDM Tech. Dig, pp. 97-100, 2010.

11. S.H. Lee et al, IEDM Tech. Dig, pp. 47-50, 2011.

12. M-J. Lee et al, IEDM Tech. Dig, pp. 771-774, 2007.

13. K. Gopalakhrishnan, VLSI Tech. Symp, pp. 205-206.

14. I.-G. Baek, IEDM Tech. Dig, pp. 737-740, 2011.

About the author

Bogdan Govoreanu is currently appointed as a principal scientist with imec Leuven and a staff member of the Memory Device Design Group, Process Technology Unit, carrying out research in the field of emerging memory devices with focus on resistive switching memory. He received his Ph.D.in Applied Sciences in 2004 from the University of Leuven (Katholieke Universiteit Leuven). During his career, Govoreanu has authored or co-authored over 80 research papers and holds/has filed six US and European patents/patent applications. He is also an IEEE Senior Member.

Labels:

dielectric,

expert,

Fab,

Flash,

HfO2,

Memory,

NAND,

NOR,

oxide,

PCM,

phase-change memory,

Process,

Resistive RAM,

RRAM,

SSD,

tantalum dioxide/ditantalum pentoxide,

testify,

titanium dioxide,

witness,

zirconium dioxide

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)